Green Energy

From the Wall Street Journal:

- Michelle Obama Refuses To Wear Hijab In Sucky Arabia, Looks Decidedly Unhappy In Their Fucked-up World

Just like a real American should. Gotta Say, I Kinda Admire Michelle Obama Today. Saudi Arabian TV blurred out her face because she didn't wear the head covering. Weasel Snippers has a whole bunch of photos of Michelle looking more than displeased...

- Saudi Arabia's New King Has Alzheimer's?

Who the Fuck Is "Allah"? And Why Do I Have This Fakakta Rag On My Head? Saudi Arabia's 'reformer' King Abdullah dies The next king will be Prince Salman bin Abdulaziz, state television reported early Friday. ***** Salman has been diagnosed...

- Us Poised To Become World’s Leading Liquid Petroleum Producer

From the Financial Times: High quality global journalism requires investment. The US is overtaking Saudi Arabia to become the world’s largest producer of liquid petroleum, in a sign of how its booming oil production has reshaped the energy sector. US...

- Calling All Ron Paul Willful Isolationist Morons

Saudi prince calls for acquisition of nuclear arms, other WMDsA senior member of the ruling Saudi Royal Family said last week that the kingdom should build nuclear weapons in response to Iran’s nuclear program.Saudi Prince Bin Turki al Faisal, a former...

- Iran And Saudi Arabia To Enrich Uranium In Switzerland??

Saudi Arabia today revealed details of an ambitious offer to Tehran, aimed at defusing the growing crisis over Iran's controversial nuclear programme. Speaking at the end of the state visit to London by King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, his Foreign...

Green Energy

Saudi Arabia’s King Salman Replaces Crown Prince, Foreign Minister

Who Am I? Why Am I Here?

And Why Am I Wearing This Facacta Rag On My Head?

From the Wall Street Journal:

In shuffling of officials, nephew is named as new heir apparent, nonroyal named as foreign minister

He replaced veteran Foreign Minister Prince Saud Al Faisal with Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the U.S. Adel al-Jubeir.

The Saudi shake up can have important implications, yes. I came upon the link at BING's News headlines for Saudi Arabia. The link there remains readable without the subscription:

RIYADH—Only three months have passed since Saudi Arabia got a new king. But in its foreign and domestic policy, it is already a kingdom transformed, and not necessarily in ways that please the U.S.

King Salman, 79, assumed the throne after his older brother, King Abdullah, died on Jan. 23. Within days, the new monarch reshuffled the ranks of power, delegating many day-to-day affairs of government to his son, Prince Mohammed bin Salman, 29, and to his nephew, Prince Mohammed bin Nayef, 55.

Under their leadership, confirmed by Wednesday’s changes in the line of succession, Saudi Arabia has become increasingly independent of Washington as it wages a war in neighboring Yemen while opening up to conservative Islamic clerics who opposed the late king’s liberal reforms.

In a kingdom where elderly and infirm monarchs made all major decisions for decades, this empowerment of younger members of the House of Saud is a significant departure.

It has already translated into a surprisingly activist foreign policy that has asserted Saudi leadership of a Sunni Muslim bloc confronting mainly Shiite Iran.

Angered by the U.S. outreach to Iran and eager to showcase its own ability to use military force, Saudi Arabia last month began airstrikes in Yemen, the first foreign war that Riyadh has run since it led a military campaign on the same soil in 1934.

“During King Abdullah, we did not have a foreign policy, and just watched events unfold in front of our eyes in Yemen,” said prominent Saudi sociologist and commentator Khalid al Dakhil. The new administration in Riyadh, he added, “is making the right choices and having the will to follow through.”

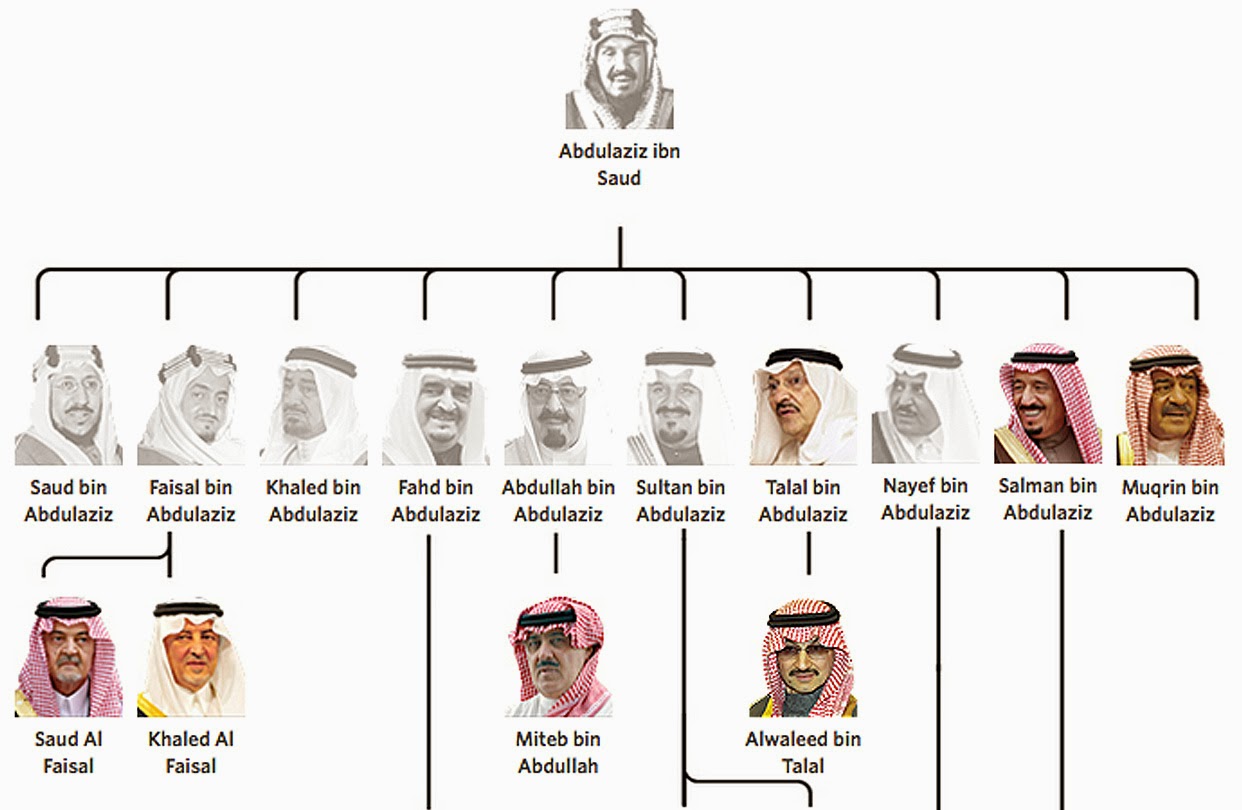

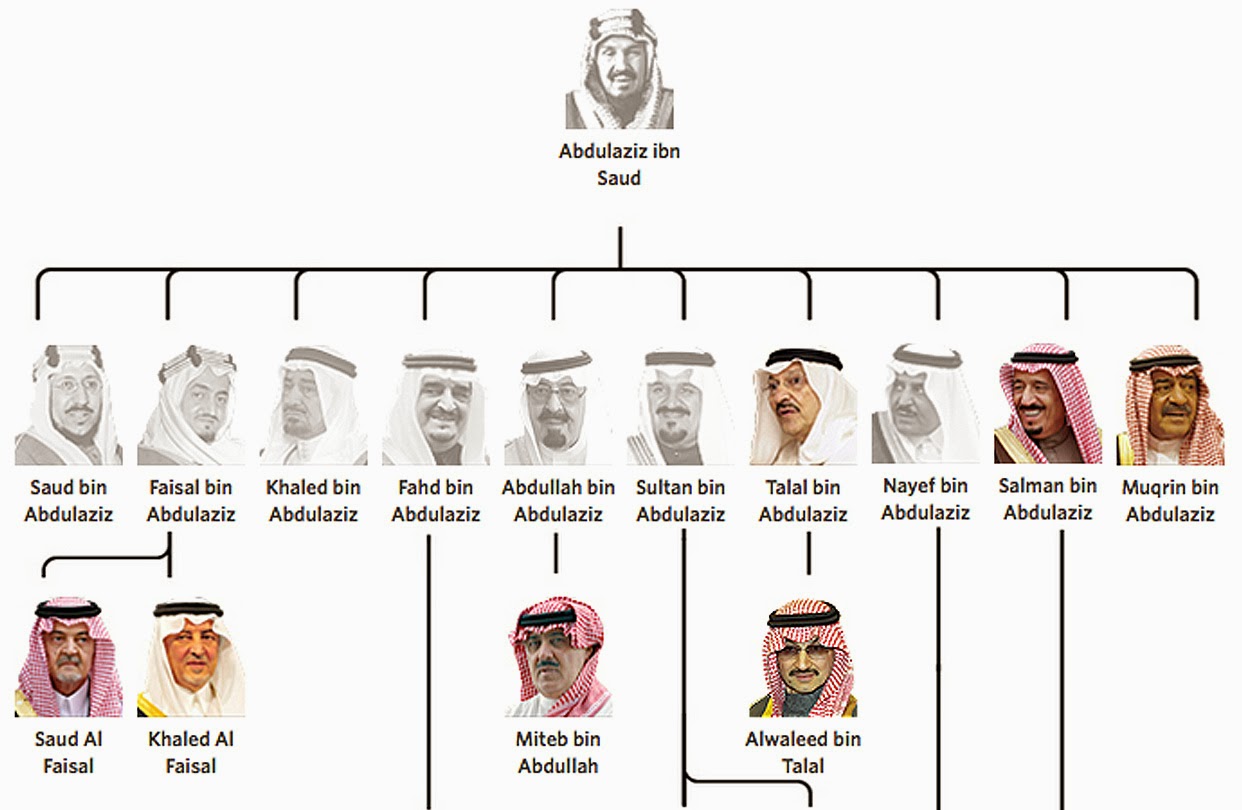

heirarchy chart image - click to make larger

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei predictably had a less charitable take on Riyadh’s new approach, complaining earlier this month that Saudi Arabia’s traditional caution in world affairs has been jettisoned by “inexperienced youngsters who want to show savagery instead of patience and self-restraint.”

Though the world’s attention has focused on these changes in Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy, the developments at home have been just as important.

Along with his moves to curb Iranian influence, King Salman shored up domestic support by appeasing Saudi religious conservatives who had come to view King Abdullah’s tentative modernization drive, which included the creation of a coeducational university, with open hostility.

Within days of taking over, King Salman replaced the head of the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, removing an official long criticized by conservatives for attempting, under King Abdullah’s direction, to defang the kingdom’s feared religious police.

Under new leadership, the Committee’s enforcers have already become more active, resuming patrols in shopping malls where they have not been seen in years and raiding beach-front compounds used by foreigners.

Wednesday’s decree by King Salman also removed from her post the most senior female official in the kingdom, the deputy education minister, whose appointment in 2009 was hailed by the West as an encouraging sign of the kingdom’s progress on women’s rights.

Mohsen al Awaji, an Islamist lawyer and activist who was imprisoned six times, most recently in 2013, praised King Salman’s new outreach to fellow conservatives as “a very positive indication.”

“During King Abdullah, a lot of the decisions were taken against the will of the people—in internal and external affairs. King Abdullah had opened a very serious conflict with the conservatives,” Mr. Awaji said. “But King Salman is a man of common sense.”

While Saudi Arabia remains one of the world’s most repressive societies, the new administration in Riyadh has also made conciliatory moves toward Islamist dissenters, relaxing or ending restrictions on some, and ending King Abdullah’s policy of trying to crush the Muslim Brotherhood.

In a nation where stability and continuity have long been the official mantra, these changes are barely acknowledged in government discourse. But combined with the Yemen war, they have already bolstered the new king’s popularity, even among longtime critics of the regime.

“What was happening under King Abdullah was not real reform but fake liberalism,” says Saudi political analyst Abdullah al Shammari, a former senior diplomat and professor.

Saudi Arabia’s conservative brand of Islam is the glue that holds the kingdom together, and the new regime has wisely recognized the perils of attempting to dilute it, Mr. Shammari observed.

“Saudi Arabia is the center of Islam, and it is not our choice to be liberal. The moment Saudi Arabia tries to be liberal, it will collapse,” he said.

The architect of King Abdullah’s policies to roll back conservative restrictions—an approach welcomed by the U.S.—and to crack down on the Muslim Brotherhood was Khalid al Tuwaijiri, the head of the Royal Court.

King Salman removed him within hours of taking over in January, appointing to that position his son, Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who held the job until his elevation on Wednesday to deputy crown prince. The young prince remains in charge of the Defense Ministry and the inter-ministerial committee overseeing economic affairs and development.

Prince Mohammed bin Nayef, who succeeded his father as interior minister and has worked closely with the U.S. to curb al Qaeda and Islamic State, runs a separate committee responsible for political and security affairs.

The new economic committee, in particular, has brought significant changes to the way Saudi Arabia’s economy is governed, with ministries formerly run as individual fiefs now put under the prince’s direct control, and ministers deemed to be underperforming fired without ceremony.

“Every minister knows they are watched much more closely than before,” said Khalid al Sweilem, former head of investment at Saudi Arabia’s central bank and a fellow at Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Prince Mohammed bin Salman “is very much involved and he is looking at what is good for the country, not at what is good for a particular ministry.”

- Michelle Obama Refuses To Wear Hijab In Sucky Arabia, Looks Decidedly Unhappy In Their Fucked-up World

Just like a real American should. Gotta Say, I Kinda Admire Michelle Obama Today. Saudi Arabian TV blurred out her face because she didn't wear the head covering. Weasel Snippers has a whole bunch of photos of Michelle looking more than displeased...

- Saudi Arabia's New King Has Alzheimer's?

Who the Fuck Is "Allah"? And Why Do I Have This Fakakta Rag On My Head? Saudi Arabia's 'reformer' King Abdullah dies The next king will be Prince Salman bin Abdulaziz, state television reported early Friday. ***** Salman has been diagnosed...

- Us Poised To Become World’s Leading Liquid Petroleum Producer

From the Financial Times: High quality global journalism requires investment. The US is overtaking Saudi Arabia to become the world’s largest producer of liquid petroleum, in a sign of how its booming oil production has reshaped the energy sector. US...

- Calling All Ron Paul Willful Isolationist Morons

Saudi prince calls for acquisition of nuclear arms, other WMDsA senior member of the ruling Saudi Royal Family said last week that the kingdom should build nuclear weapons in response to Iran’s nuclear program.Saudi Prince Bin Turki al Faisal, a former...

- Iran And Saudi Arabia To Enrich Uranium In Switzerland??

Saudi Arabia today revealed details of an ambitious offer to Tehran, aimed at defusing the growing crisis over Iran's controversial nuclear programme. Speaking at the end of the state visit to London by King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, his Foreign...