Submission In The Netherlands

“The Freedom Party (PVV),” read yesterday’s press release, “is shocked by the Amsterdam Court of Appeal’s decision to prosecute Geert Wilders for his statements and opinions. Geert Wilders considers this ruling an all-out assault on freedom of speech.”

The appalling decision to try Wilders, the Freedom Party’s head and the Dutch Parliament’s only internationally famous member, for “incitement to hatred and discrimination” against Islam is indeed an assault on free speech. But no one who has followed events in the Netherlands over the last decade can have been terribly surprised by it. Far from coming out of the blue, this is the predictable next step in a long, shameful process of accommodating Islam—and of increasingly aggressive attempts to silence Islam’s critics—on the part of the Dutch establishment.

What a different road the Netherlands might have taken if Pim Fortuyn had lived! Back in the early spring of 2002, the sociologist-turned-politician—who didn’t mince words about the threat to democracy represented by his country’s rapidly expanding sharia enclaves—was riding high in the polls and appeared on the verge of becoming the next prime minister. For his supporters, Fortuyn represented a solitary voice of courage and an embodiment of hope for freedom’s preservation in the land of the dikes and windmills. But for the Dutch political class and its allies in the media and academia—variously blinded by multiculturalism, loath to be labeled racists, or terrified of offending Muslims—Fortuyn himself was the threat. They painted him as a dangerous racist, a new Mussolini out to tyrannize a defenseless minority. The result: on May 6, 2002, nine days before the election, Fortuyn was gunned down by a far-left activist taken in by the propaganda. The Dutch establishment remained in power. For many Dutchmen, hope died that day.

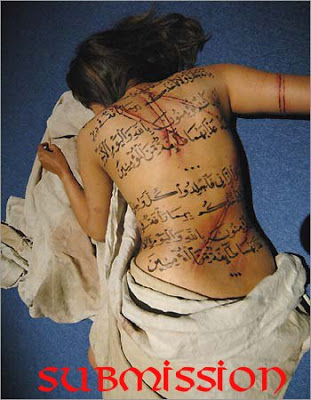

Fortuyn’s cause was taken up by journalist, director, and TV raconteur Theo van Gogh, who was at work on a film about Fortuyn when he was slaughtered on a busy Amsterdam street on November 2, 2004. The killer, a young Dutch-born Islamist, had been infuriated by Submission, van Gogh’s film about Islamic oppression of women. Epitomizing the Dutch elite’s reaction to the murder was Queen Beatrix’s refusal to attend van Gogh’s funeral. Instead, she paid a friendly visit to a Moroccan community center.

The spotlight then shifted to Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the brilliant Somali-born member of the Dutch parliament and cowriter of the script forSubmission, who, rejecting the Islam of her birth, had become an eloquent advocate for freedom, especially for the rights of Muslim women facing no less oppression in the Netherlands than they had back in their homelands. Hirsi Ali was lucky: she wasn’t murdered, only hounded out of the parliament, and out of the country, by a political establishment that viewed her—like Fortuyn and van Gogh before her—as a disruptive presence.

That was in 2006. In that year, as if to demonstrate the gulf between popular and elite views, a poll showed that 63 percent of Dutchmen considered Islam “incompatible with modern European life.” Yet Piet Hein Donner, Dutch Minister of Justice, insisted that “if two-thirds of all Dutchmen wanted to introduce sharia tomorrow . . . it would be a disgrace to say ‘this is not permitted’!”

With Hirsi Ali abroad, the torch passed to Geert Wilders. At times, it seems that he is the last prominent Dutch figure willing to speak bluntly about the perils of fundamentalist Islam. The same people who demonized Fortuyn have done their best to stifle Wilders. In April 2007, intelligence and security officials called him in and demanded that he tone down his rhetoric on Islam. Last February, the Minister of Justice subjected him to what he described as another “hour of intimidation.” The announcement that he was making a film about Islam only led his enemies to turn up the heat. Even before Fitna was released early last year, Doekle Terpstra, a leading member of the Dutch establishment, called for mass rallies to protest the movie. Terpstra organized a coalition of political, business, academic, and religious leaders, the sole purpose of which was to try to freeze Wilders out of public debate. Dutch cities are riddled with terrorist cells and crowded with fundamentalist Muslims who cheered 9/11 and idolize Osama bin Laden, but for Terpstra and his political allies, the real problem was the one Member of Parliament who wouldn’t shut up. “Geert Wilders is evil,” pronounced Terpstra, “and evil has to be stopped.” Fortuyn, van Gogh, and Hirsi Ali had been stopped; now it was Wilders’s turn.

But Wilders—who for years now has lived under 24-hour armed guard—would not be gagged. Thus the disgraceful decision to put him on trial. In Dutch Muslim schools and mosques, incendiary rhetoric about the Netherlands, America, Jews, gays, democracy, and sexual equality is routine; a generation of Dutch Muslims are being brought up with toxic attitudes toward the society in which they live. And no one is ever prosecuted for any of this. Instead, a court in the Netherlands—a nation once famous for being an oasis of free speech—has now decided to prosecute a member of the national legislature for speaking his mind. By doing so, it proves exactly what Wilders has argued all along: that fear and “sensitivity” to a religion of submission are destroying Dutch freedom.

-

Geert Wilders Wants Islamist Who Murdered Theo Van Gogh to Testify at His Trial For Insulting Islam...From Weasel Zippers: Brilliant.... As the trial of Dutch anti-Islamist lawmaker Geert Wilders resumes Wednesday, the crucial question will be...

- Geert Wilders: Loved By The People, Hated By The Parliamentarians

From Atlas Shrugs: This is so gorgeous you can't help but smile, like the Mona Lisa. It says it all. It also points to a collision course for the moochers, looters and destroyers, aka the 'political elite' and the enslavers. It won't...

- Signs Of Life In Europe: Wilders' Freedom Party Makes Big Gains The Eu Election!

From the Astute Bloggers: BBC:Geert Wilders' Freedom party will win four of the 25 Dutch seats in the parliament, just one behind the country's Christian Democrats.... Exit polls showed late on Thursday that Mr Wilders' Freedom Party (PVV)...

- Bbc Readers Comments On The Arrest And Persecution Of Geert Wilders

You can find them all by clicking here. Here are a select few: It's devastating to see that even in the UK freedom of speech can be blocked by a minority which blackmails a free society by threatening with riots & chaos. Mr Geert Wilders is not...

- Dutch Say Islam Is Incompatible With Modern Europe

A new poll shows the Dutch citizenry gets it. 63% say Islam is incompatible with modern Europe. Check out this report from polling firm, Angus-Reid Consultants: Many adults in the Netherlands hold strong views on the way Muslims adapt to the European...